To think the idea was to fight off slavery from the “white man”, not knowing there’s a greater independence, girls in the Volta region of Ghana need to get from their leaders.

The government outlawed the Trokosi custom in 1998 yet it is still occurring in some towns today.

What is Trokosi?

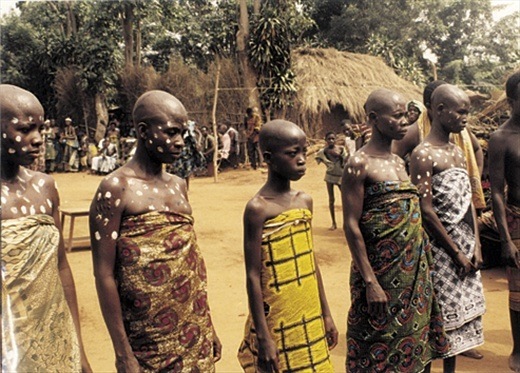

Trokosi is a traditional system where virgin girls, some as young as six years old, are sent into shrines as slaves, to make amends for wrongs committed by a member of the virgin girl’s family. Until the Trokosi system came to the attention of the general public in the 1990s, girls sent to the shrines stayed for life. After the 90’s some of the priests and elders were willing to let the girls go back home after a few years, for a few months, but had to return whenever they were sent for. When they die, the family must replace her with another virgin girl.

The Trokosi system is based on the belief that gods have the power to search for wrongdoers and punish them. People who feel an injustice has been committed against them, go to the shrine and place a curse on the offender so that they will be punished by the gods. These curses take several forms, strange sicknesses, unexplained deaths, incurable diseases or successive deaths within a family.

When the virgin girls are sent to the shrines, they become the “wives of the gods” and are sexually exploited by the priests and shrine elders. The shrine priest is the spiritual head of the shrine and “proxy for the gods” while clansmen can be appointed as elders of the shrine. The girls are forced to work in any capacity that suits these priests and elders for instance, on their farms.

If there are children born out of the relationship with them, they become the responsibility of the virgin girls’ family. The Trokosi girls live in constant hunger, deprivation, and poverty.

In a report by Veronique Mistiaen, after travelling across Ghana’s Volta region, filled with rich history and culture, in 2013, to try to understand why the practice of trokosi still endures today, she realised, it is deeply rooted in the beliefs and identity of the Ewe (ay-vay) people.

Here are some women who were interviewed by Rhonda.

Enyonam Tordzro, when 18 years, was sent by her parents, to a shrine in Tsaduma, a few hours by truck from their own village. “They said, I needed to go there to atone for the sin of someone in the family,” says Enyonam who is now 35. After a humiliating initiation in which she was stripped of all her clothes representing her former life, she became a trokosi – the wife and slave of the shrine’s war god, and therefore of its priest. “I had no clothes: only a piece of cloth to cover my privates and I had to wear a cord around my neck. I was the lowest of the servants,” says Enyonam, who was one of the priest’s 200 slaves.

“Our days started at 4 am: we fetched water and swept the compound, then tended the priest’s land until dusk. The priest didn’t provide for us. We were always hungry. There was no sympathy between trokosi’, we saw each other mostly as rivals for food and the priest’s attention. I never felt comfortable around him – he had a long wand and whipped us for all sorts of reasons – but I still wanted his attention. We were all his wives. I had six children with the priest.” Trokosi’ children grow up in servitude too, and the priests who fathered them don’t care for them.

“I wanted to run away, but I had to stay to save the lives of my young siblings who were dying. Four of my cousins had already died and at least two of my uncles. So I needed to stay to save the rest of my family,” she says quietly.

Enyonam was liberated a few years ago after long negotiations between International Needs Ghana (ING), the leading Ghanaian charity campaigning against the practice, and the priest and elders. When she returned to her village, her father rejected her.

“He said I needed to go back to the shrine otherwise harm would come to our family. He was afraid the curse would revisit them. They were all afraid. They still are. When people find out we are ex-trokosis, they are afraid to approach us, so it is hard to do business here,” says Enyonam, who works a seamstress with Forgive Gbetev, her best friend and another former trokosi.

History of the Trokosi Practice

The word Trokosi comes from the Ewe language, Ewe communities found in Benin, Togo and Ghana. It’s a combination of two Ewe words “tro” and “kosi.” “Tro” means god or deity, and “kosi” means slave. Trokosi therefore means “slave of God.”

Most of the people that live in the southern Volta Region of Ghana, southern Togo, and southern Benin believe and practice the Trokosi system.

A Call to an end of this Practice.

In 1998 the Ghanaian government passed a law criminalising the Trokosi practice.

Despite this, it continued because governmental agencies responsible for enforcing the law didn’t have the courage to arrest the family members, priests or shrine owners. The system invokes fear in the hearts of most people including the law enforcement personnel.

Trokosi practising communities strongly believe in the power of gods to cause calamities to families. Trokosi priests ensure they are reminded of this by issuing warnings that they must send their virgin girls as objects of reparation.

The practice also thrives because there’s a group of traditionalists, mostly male, who strongly believe that Trokosi is part of the Ewe’s cultural heritage and must be preserved. They therefore oppose every attempt to stop the practice.

The Way Forward.

Over the past two decades, Ghana’s human rights commission and various NGOs adopted different intervention approaches to end the practice.

According to Wisdom Mensah

Visiting Instructor, University of West Florida, below are some points to note to aid in the complete eradication of the Trokosi system.

• Joint campaigns involving both NGOs and Ghana’s commission on human rights

• Encouraging Trokosi priests and elders to accept other objects of reparation, instead of people. For instance, several shrines have modernised the practice by replacing virgin girls with cows as objects of reparation.

• Negotiations with priests and shrine elders to set slaves free and sign legal documents to ensure they won’t go back to the practice. In exchange they receive a package that will help them generate income, replacing the loss of human capital. For instance, a number of cows that they can breed.

• Whilst the Trokosi women are still enslaved they can be provided with vocational skills training. They gain much needed skills which will help them generate income and support their children in the future – and it also creates some distance between them and the shrine as they attend the training in centres every day. Once free, the women need micro-financing and also emotional and mental support.

• Finally, since this issue is a gross human rights violation against women and children, the International Community should put pressure on the government and people of Ghana to enforce the 1998 law making the Trokosi practice a crime. If pressure is brought by international organisations such as the United Nations, African Union, ECOWAS, European Union etc. the practice of Trokosi in West Africa can be brought to an end quickly

https://theconversation.com/girls-in-west-africa-offered-into-sexual-slavery-as-wives-of-gods-105400

https://news.trust.org/item/20131003122159-3cmei/

Martinez, Rhonda (2011) “The Trokosi Tradition In Ghana: The Silencing of a Religion,” History in the

Making: Vol. 4 , Article 5.

Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol4/iss1/5